The first category is...

Most Intellectually Offensive

Honorable Mention: Rules of Engagement (2000, dir. William Friedkin): William Friedkin's post-seventies career is a model of inconsistency and supreme artistic laziness, but with this 2000 thriller Friedkin crossed the boundary of mediocrity into the putrid realm of war crimes justification. In the hopelessly A Few Good Men-like Rules of Engagement, Samuel L. Jackson plays Terry Childers, a marine colonel who orders his troops to open fire on a crowd in Yemen when evacuating a US embassy and is subsequently charged with war crimes. Ultimately he is acquitted and the audience is made to understand that his brutal tactics stem only from the concern he has for his troops' safety. In a particularly reprehensible sequence, Childers flashes back to an incident in the Vietnam War in which he murdered a prisoner-of-war while his unit was under attack. And this too, we are urged to believe, was a merely a case of the ends justifying the means.

Honorable Mention: Rules of Engagement (2000, dir. William Friedkin): William Friedkin's post-seventies career is a model of inconsistency and supreme artistic laziness, but with this 2000 thriller Friedkin crossed the boundary of mediocrity into the putrid realm of war crimes justification. In the hopelessly A Few Good Men-like Rules of Engagement, Samuel L. Jackson plays Terry Childers, a marine colonel who orders his troops to open fire on a crowd in Yemen when evacuating a US embassy and is subsequently charged with war crimes. Ultimately he is acquitted and the audience is made to understand that his brutal tactics stem only from the concern he has for his troops' safety. In a particularly reprehensible sequence, Childers flashes back to an incident in the Vietnam War in which he murdered a prisoner-of-war while his unit was under attack. And this too, we are urged to believe, was a merely a case of the ends justifying the means.In all honesty, I think The Patriot is a very entertaining film, but that's because I don't analyze it that deeply, which is good because The Patriot doesn't stand up well to historical or intellectual scrutiny. In particular, the film's treatment of race in the thirteen colonies during the Revolutionary War is disgustingly inaccurate to the point of marginalizing the tragedy of slavery. In the film, Mel Gibson plays a Southern planter, Benjamin Martin, whose moral lapses stem only from his dark, war-like past, not from the fact that he participates in the slave trade: because he doesn't. The African laborers on his farm work the land as "freed men". In addition, there is the character of Occam, a slave who is conscripted to fight in Benjamin's militia. At the end of the film, Occam finds out that his service in the militia has guaranteed his freedom, which I suppose is symbolic of the promise of freedom for all slaves, but instead plays as a tasteless joke. Rather than treating the issue of slavery honestly, this film anesthetizes it to the point of cruel triviality.

My problems with Inglourious Basterds extend beyond points of ideology, but I can't let the film get away with a few things: one is Quentin Tarantino's earnest belief that barbaric violence necessarily leads to military victory, which he made perfectly clear in a Cannes press conference where he said that if the 'Basterds' had existed in World War 2 they would have "changed the course of the war." Secondly, the film's cavalier distortion of history made me very uncomfortable. In my first blog response to the film, I wrote:

"I sat in the theater watching the beautifully violent and expressive deaths of Adolph Hitler and other war criminals with my mouth wide open with incredulity, not understanding completely how everyone was so entertained by this half-baked fever dream. Certainly I felt some level of self-righteous glee at seeing the world's most notorious mass murderer exploded with bullets, but I couldn't help but think that it was both morally and intellectually dishonest."

"I sat in the theater watching the beautifully violent and expressive deaths of Adolph Hitler and other war criminals with my mouth wide open with incredulity, not understanding completely how everyone was so entertained by this half-baked fever dream. Certainly I felt some level of self-righteous glee at seeing the world's most notorious mass murderer exploded with bullets, but I couldn't help but think that it was both morally and intellectually dishonest."

This alternative retelling of World War 2 seems to satisfy a base need for socio-historical catharsis, but does it do so at the expense of accepting the darker realities of our collective pasts, all so that Quentin Tarantino can fetishize violence in World War 2?

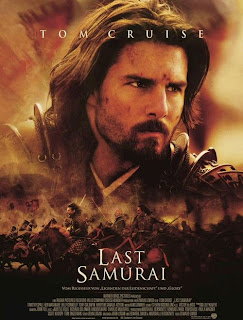

Whether or not someone enjoys this film most likely hinges on two factors: the first being whether one can genuinely respect a Dances With Wolves knock-off; and the second being whether one believes dying in a unnecessary blaze of glory is noble. As for myself, I tend not love Dances With Wolves knock-offs, and I generally think that dying in a blaze of glory for the sake of dying in a blaze of glory is psychotic, which is precisely what happens in this film. Simply put, a samurai leader (Ken Watanabe) struggling against Japanese modernization attacks the emperor's new, technologically superior army in a sure-to-be-doomed offensive. This fact does not humble the main characters, but rather their willingness to engage themselves in a glorified suicide mission becomes a point of pride.

I don't necessarily think that the United States' covert involvement in the Russian/Afghanistan war was a bad thing, but this film not only explicitly glorifies the CIA's secret operation in that conflict, but it also implicitly suggests that the US's anti-communist activities in Latin America and South America was justified, or the film simply doesn't acknowledge the devastating cost of those actions. In addition, the film's assertion that the Russian/Afghanistan war was the sole cause of the end of the Soviet Union is myopic.

1. The Pursuit of Happyness (2006, dir. Gabriele Muccino)

1. The Pursuit of Happyness (2006, dir. Gabriele Muccino)Apparently, I was the only one who found this story of a single father trying to acquire a stock broker's position in order to support his son to be anything but uplifting. Why? Because he essentially gambles his son's future on a million to one shot, and because he miraculously achieved it, it's seen as a triumph of the spirit. I see it, on the other hand, as a feat of remarkable, disaster-avoiding luck--not to mention a free market conservative's hysteric wet dream.

Oh The Last Samurai....

ReplyDelete